How to find & validate the market from your academic projects.

Solved a big problem or made a surprising discovery in your academic work recently? You’ll probably want to consider the commercial potential of your hard work!

The best way to do that is to understand and validate whether your idea could be a successful business opportunity.

Most successful startups build the solution based on insights from speaking to customers - read more about why that’s important in our blog here. However - we know that’s not always how things shake out, and in the case where you’ve already built something, you’ll want to understand how valid it is as a business proposition - or how much of the solution would need to be changed to make it attractive to customers. Many people call this a product/ market fit.

Validation helps to de-risk a business or idea before significant time and money is spent on developing a product. It is a process of gathering evidence that you are on the right track, and/or identify if you are heading in the wrong direction. Taking early corrective action (or abandoning a project altogether) can save you precious money, time and resources.

Validation Overview

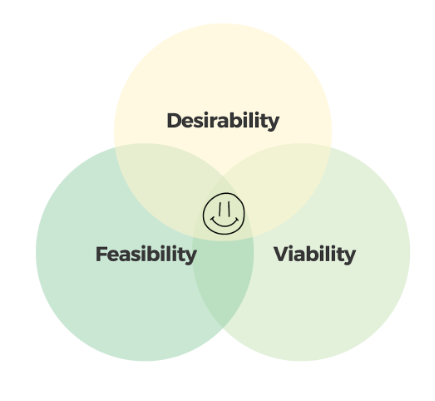

Validation can be seen as three parts of a Venn diagram; where all three parts overlap is the “sweet spot” that indicates the best chance of a successful product or venture. The three parts of the Venn diagram are Desirability, Viability, and Feasibility.

Desirability means that your potential customers and users want the value that your venture offers. The process of validating Desirability includes understanding the customers and the pain points that your offering solves. It also takes into consideration alternative solutions, and willingness to pay. More below!

Viability means that your venture has a sound financial model. The process of validating Viability means understanding all the costs associated with the business model, and how it can eventually generate income to support it long-term.

Feasibility means that you are able to deliver your venture’s value proposition. The process of validating Feasibility may involve prototypes and proofs of concept that solve technical challenges, experiments with logistics, and exploring whether you or your team have all the skills to make it happen (or how you can outsource them).

Desirability

This is all about having customers that want your solution. As a startup, it’s really worth spending time understanding the pain points of your ideal customer, so you can better understand why they would choose your solution rather than alternatives. These ideal customers can be very valuable and can give you useful insights; furthermore, they are the best people to test the solution for feedback.

One of the best ways to start testing desirability is to interview customers about their pain points and to understand why current solutions / what they are doing currently doesn't work. In this phase of development, it is not about selling or talking about your solution - it's about understanding the customers' needs. This information helps when you get to selling, as you will know the best way to articulate the features of your solution. You might be used to sending off a grant application or research manuscript and waiting months to hear an outcome; the good news is that with customer discovery interviews you can find out in 15 minutes whether you’re on the right track.

As part of desirability, you can also look to the market for more information on who your competitors are and whether you can scale what you are doing to be at a price point that is desirable for the customers.

Viability

A startup is more than a product. You can have the best product and still fail as a business. Viability means your financial model stacks up – and you have the resources to sustain and grow the business long-term, even if initially your costs might outweigh your revenue.

At this stage, validation requires you to consider how you transition your idea/ product out of the academic environment and into a business model. There are many things to consider in this section related to finances such as fixed and ongoing costs ( rent, equipment hire, licences, your own salaries); one-off costs (assets and machinery); and variable costs ( the cost of materials, casual labour, packaging and shipping). Some of those you might be able to estimate based on your experience.

Some other costs may be less obvious, but could mean the difference between being profitable and losing hundreds of dollars with every transaction. How much will it cost you in marketing, advertising and sales reps’ salaries to acquire a new customer? This is your Customer Acquisition Cost, aka “CAC”, and it might take some testing and learning to find out. Once you land a customer, how much will they purchase from you, and over what period? From this you can work out the Customer Lifetime Value (known as “LTV” or “CLTV”), and the “CAC Payback Period”, i.e. when do you break even on the cost of acquiring a customer? Again, these aren’t likely to be answers you know – and that’s OK!

To validate viability, you can do a rough back-of-the-napkin (or, really, spreadsheet) estimate of these numbers and see if your financial model makes sense.

A quick bit of research for comparable products or services, sold to comparable customers, might be enough for a low-fidelity financial model and a corresponding level of confidence that your venture is viable.

Then, when it makes sense to, do some more robust research, run some experiments – how much does it really cost to get customers on board – and increase the fidelity of your model, the strength of your evidence, and your confidence in your model.

Feasibility

When taking a solution out of the research setting and into a spin-out/ startup or licensing it to an existing business- there are a few things to consider as part of feasibility.

If you are taking your idea out of the research environment it will be crucial to understand your Intellectual property rights and options for protecting your idea -your local tech transfer office (TTO) can help with this. If you’ve built your product through research or academic work, you are likely to have already tested the concepts that are fundamental to the thing or product working as well as the technical feasibility. One key consideration is how your idea/product compares to what you identify as the closest alternative. If you can highlight how you are different and/or better, this is powerful knowledge to bring when talking to your local TTO.

Now it's time to consider the commercial feasibility. This can include price points, and the ability to scale the solution commercially to a point where it is still at a price point that your customers are willing to pay - and is also financially viable at the same time.

Furthermore, is there a certain part of the solution that can be tested to get a gauge of interest from the market? This would be called your minimum viable product or solution (MVP).

Oh, and don’t be fooled by the term “validation”. You don't get a green tick and a guarantee of business success. The goal of validation is not to get a binary “validated/invalidated” outcome but to test and learn whether individual elements of your hypotheses are reliable, and what you might do to adjust or improve your approach. It’s also not a one-and-done process; it’s a constant, iterative process you can use to chart the ambiguity, uncertainty and risk inherent in early-stage entrepreneurship.